How to disappear Completely

MIKE OLIN / BEN PRITCHARD

Essay by Paul D’Agostino

September 15 - October 8, 2023

Opening reception: Friday, September 15, 6 - 9 PM

Artist talk: October 8, 2 PM

The talk will be recorded and streamed live on our Instagram page.

VIEW NOW: ARTSY VIEWING ROOM

Transporting, Transposing: Mike Olin and Ben Pritchard Turn Windows Into Doors in How to Disappear Completely

by Paul D’Agostino

The physical possibility of disappearing wholly and completely seems rather improbable, but the notion does present an intriguing matter to ponder. If someone or something were to actually vanish from sight, for example, wouldn’t leaving behind a trail, memory, or trace make such an instance of disappearance only partial? If so, what might it mean to vanish merely in part? Is who or what left more or less real than what’s left? Might partial disappearance imply the inverse possibility of only partially appearing? On that note, what’s full appearance in the first place?

Mike Olin and Ben Pritchard don’t purport to have answers to such questions with their paintings in How to Disappear Completely, an exhibit titled after the eponymous Radiohead song. However, these seasoned painters do provide viewers with ample pictorial contexts for not necessarily disappearing, but for being at least temporarily transported and transposed – that is, for being carried away into modes of transfixed looking akin to a sense of tentative disappearance. Truly vanishing into some ether is neither intended or implied. Rather, these artists create their art by losing themselves in processes, thoughts, and paint itself, and here they’re inviting viewers along for the ride.

Olin and Pritchard go about these things through different means and to different ends, and teasing apart these distinctions is helped along by tapping into pictorial metaphors. To be sure, there’s a long history of referring to paintings as something other than objects to be looked at. This is at least in part because we don’t only look at them, but also into, around, and in a certain sense through them as we investigate the colors, forms, textures, and contours that constitute their surfaces. We sometimes call these surfaces picture planes. Within these planes, we speak of grounds, fields, registers, areas, horizons, and much else besides. The lexicon is vast and rich. The richer the viewing experience, the vaster it gets. While the alternate terms and operative metaphors for paintings are many and various, the strongest ones intimate that a certain work or series of works might best be regarded in a certain manner, through a certain conceptual lens, or as a certain type of viewing experience. And so, if someone refers to a painting as a window, for instance, we might assume that its picture plane furnishes a context for an act of looking ‘out of’, ‘out into,’ or ‘through’, as if we’re looking outside, or up above, or into some other type of spatial beyond. It’s also not uncommon for paintings to be likened to windows through which viewers can look around for glimpses into artists’ minds. This holds for representational, abstract, and non-objective paintings alike.

And yet, rather than as a window, it’s sometimes more experientially apt to refer to a painting as a door – or even better, subtle though the difference may be, as a doorway or portal. This implies not just looking out of or through, but also opening up, crossing into, entering, or passing through. Sure, we’re only talking about mildly different understandings of kindred modes of concerted looking, but the underlying distinction is important: one mode proposes an experience that is primarily visual, while the other implies a sense of transference as well, and thus a visual experience that becomes virtually physical. Olin and Pritchard create doorways and portals that transport and transpose us. A thoroughgoing entrance into one painting by each artist will help elucidate how this works.

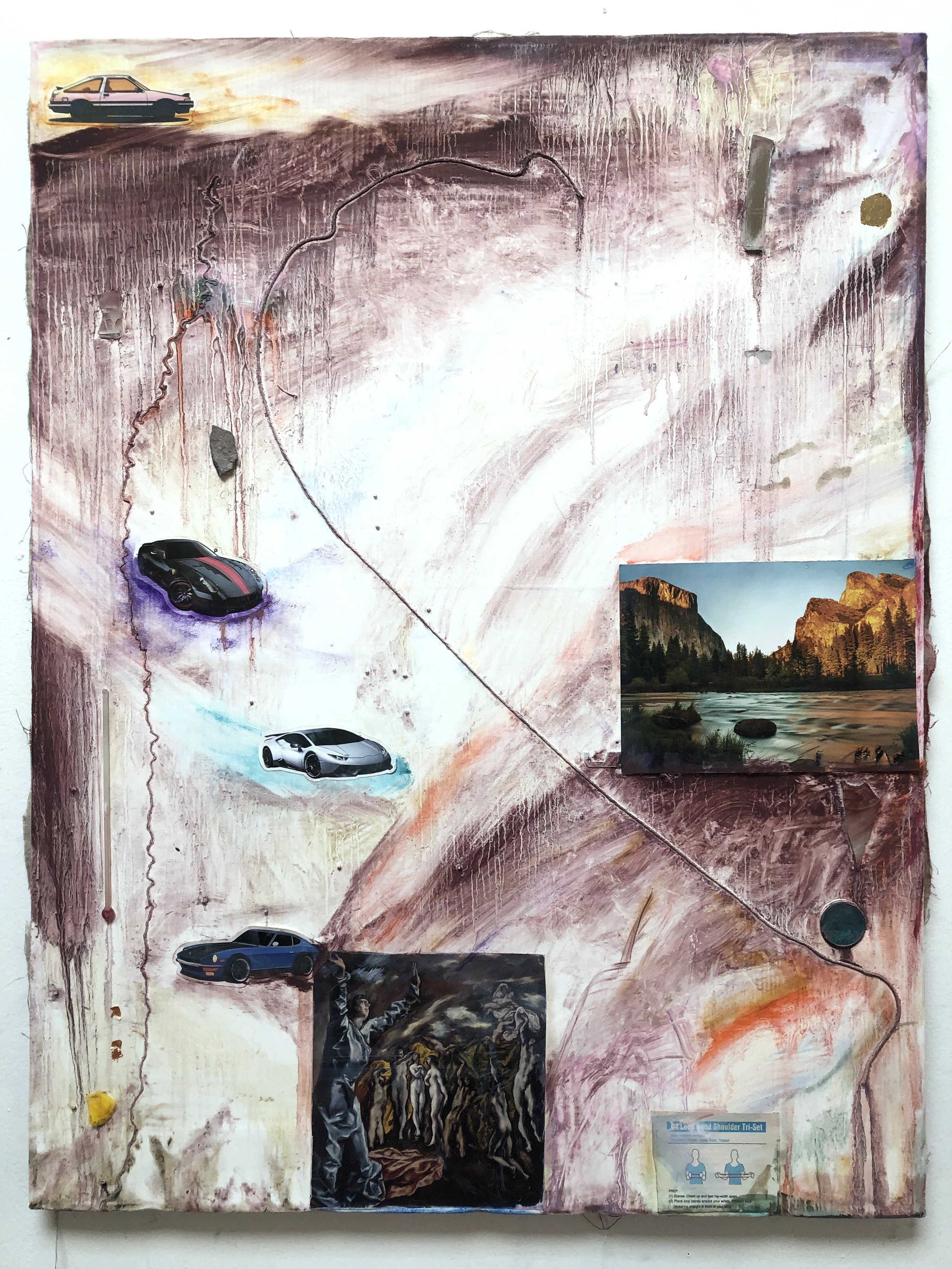

Olin’s mixed-media paintings furnish ample territory for modes of departure into mystery, reverie, and reflection. Working in traditional painting media combined with a range of textural additives, sparkling and reflective elements, and various types of collage, Olin creates portals opening into patently surreal worlds upon substrates of surface curiousness. Mustard seeds, studio scraps, and tangles and lengths of string are among the first things he lays down prior to establishing his spheres of imagery, which often present strange horizons, bizarre spatial relationships, visions of worlds-within-worlds, formal discord, and narrative asynchrony. Glitter, shards of mirror, and foil inlays send light darting around and about these multifariously enriched surfaces. Olin’s wildly imaginative worlds are often both chaotic and becalmed, creating an overall sense of what one might call sympathetic catastrophe.

The transportive portal Olin offers in his colossal work Big Cave, for example, seems to place us in the mouth of a cave looking out, as it were, as opposed to standing before the mouth of a cave, looking in. Or perhaps the cave referenced in the title is one we’re meant to seek out and discover, eventually locating it somewhere out in this peculiar, porously atmospheric landscape that seems mountainous and flat, aqueous and icy, almost horizonless or maybe twice-horizoned, and centrally placid while laterally rendering itself asunder. The immense surface here is ostensibly smooth and sheer, yet also intermittently roiling and bubbling from items embedded beneath the slightly streaky veneer. Near the bottom is a grayish borderland or elegantly slender horizon pitched before a fathomless body of water, vast stormy sky, or cleaving glacier. Large conical forms of various colors point up and down, rising and falling, striking off-balanced moments of counterpoint from left to right, while brushy and drippy interventions surge in from the sides and creep down from the top – where yet another potential horizon, impossible though it should be, seems fully plausible. The scene is deeply earthy and extraterrestrial, a cracked vision of our planet or an interloper’s glimpse of maybe Neptune, maybe Jupiter, maybe Venus. Complicating this further are the animals, athletes, calendars, domestic objects, and other formal bric-a-brac entering the picture plane by way of numerous elements of collage, as well as a smattering of small thermometers. Fractious, unsettled, and uncertain, Olin’s Big Cave is rippled with primordial energies and riddled with a sense of strangeness that’s sneakily humorous. The longer we look at it, the more the artist’s pictorial portal transports us into it to trek around – carefully, ever so carefully – in this meta-cavernous world. Disappearing into it is almost our only option.

Pritchard furnishes viewers with rather different types of pictorial portals. Instead of transporting us into other worlds, Pritchard’s works transpose us into the very stuff of their being – that is, into the richly mediated strata, variably interpretable forms, and poly-textural interstices that define their compositions and surfaces. The painter’s interest in facture is palpable and trenchant: his application is generous and thick; his grounds and layers are built up gradually; his marks and brushstrokes are intuitive, yet deliberate and considered; and his characteristically elusive forms emerge from the depths of his process, presenting as symbolic and evocative, cosmic and enigmatic. Pritchard’s portals lure us into the niches of their visible thicknesses, transposing us into their visual grip as if we’re vanishing into optical quicksand.

This effect is most most pronounced when Pritchard works at larger scales, which is certainly the case with Light Years in My Mind. This mammoth work is comprised of two towering canvases, one slightly wider than the other, conjoined at an openly disclosed juncture that opens into and interrupts the broad formal sprawl ranging across this asymmetrical diptych. As such, if one views the painting from relatively close up, it readily presents as two registers of a bilateral yet unified portal, each an open invitation into the nether textures of its surface. Given the work’s formidable scale, though, a more suitable if not dutiful point of view would be from at least a few meters away, or further yet – for the further away the viewer stands, the more the two enormous registers become visually conjoined, and the more the hulk of the work overall is subsumed by the amorphous forms and circuitous linearities that swarm and swirl about the picture plane. These looping, spiraling, intersecting, and interconnecting lines, marks, and forms are rendered in a palette of blanched crimsons, reddish oranges, and bright vermilions. The substrate they meander over and through is a rather brushily striated expanse of pasty-chalky white cut through by shades of deep red underneath it. The lines and forms seem organic and atmospheric. We’re in an enormous petri dish under a gargantuan microscope, or we’re adrift in deep space, passing by an atmospherically restive exoplanet. The large roundish and elliptical forms also scan as gigantic masses of microorganisms bundled up into colonies, with the curvilinear pathways all around them being their routes of navigation from one teeming outpost to another. We also feel as though transposed into some geothermally tumultuous terrain, rife with geysers and hydrogeological capillaries, magmatic deposits and steamy mists. Pritchard created this grandiose work while pondering astronomical imagery, cartography, and literature; while wrangling with the agonies, ironies, and joys of being alive; and while immersed in the entrancing rapture of psychedelic music. Somehow that all seems to appear both discreetly and manifestly the more we disappear into the compositional ‘light years’ of Pritchard’s stirringly wondrous, epic portal.

The notion of disappearing completely is probably better suited to imaginative thought experiments or metaphorical hyperbole than to descriptions of feasible physical realities in the context of an art show. Nonetheless, in How to Disappear Completely, Mike Olin and Ben Pritchard offer pictorially intriguing, dynamically engaging portals through which their viewers might feel transported or transposed – and into which they might temporarily vanish, at least in mind or in part. So for now, at least, we can leave the ontology of complete disappearance for another discussion – or better yet, we can leave it at the door.

– Paul D’Agostino, PhD is an artist, writer, curator, and translator. You can find him on Instagram and Threads @pauldagostinostudio.

Mike Olin (b.1971, Pasadena, California) received his BFA from Point Loma Nazarene University in 1993 and his MFA from Ohio University in 1998. His most recent exhibitions have been held at Baker Center for the Arts, Allentown PA; Peninsula Gallery, Brooklyn NY; Sardine Gallery, Brooklyn NY; Klaus von Nichtssagend, NYC; Yui Gallery, NYC; Edward Thorp Gallery, NYC; Park Place Gallery, Brooklyn; Lazy Susan Gallery, NYC. He has lived and worked in Bushwick, Brooklyn since 1999. He has exhibited his work throughout NYC and beyond for two decades.

Ben Pritchard (b. 1970, Detroit, Michigan) graduated in 2009 from the Royal Academy of Arts in London, attended the New York Studio School from 1995-1997, and has exhibited widely in New York. He has also received a Joan Mitchell Foundation grant to attend a residency at the Atlantic Center for the Arts. He was born in Detroit, Michigan. His raw, thickly-impastoed abstractions make use of interlocking geometric shapes as well as more gestural line work and organic forms, and sometimes viscous drips across the canvas. His palette uses saturated primary colors as well as more tonal compositions. While his paintings are often named after people or places, Pritchard considers his work to be mainly the result of accumulations of memory.

Press:

Press release

Photos by Adam Reich